At some time between 5 and 7 pm on November 13, 1985, the Mayor of Armero, Colombia, Ramon Antonio Rodriguez, was notified to evacuate the city because of the potential for an eminent mudflow geologists call a lahar from recent activity on nearby Nevado del Ruiz volcano. Rodriguez was aware of the lahars that had destroyed the town in 1595 and 1845, of the hazard map created in October showing the threat to Armero, and the fact that Armero resided on a delta at the base of the volcano built up from centuries of previous lahars. And yet reports document that the mayor told the citizens of Armero to remain in their homes where they would be safe. At 11:30 that night, a thunderous wall of mud 40 meters high swept through the town at 40 mph killing 23,000 residents and depositing a lahar on the city and surrounding land[1] [2].

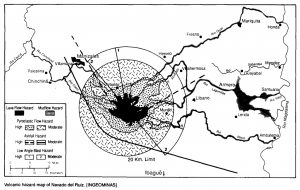

The volcanic hazards map of Nevada del Ruiz completed by Italian volcanologists first published about a month before Armero was destroyed (from Voight[3]).

Ramon Rodriguez died that night, and we are left to wonder what he was thinking. We should not be too hard on him – he was faced with a difficult decision: evacuate a city of 28,700 and risk the political ramifications if he was wrong or calm the people about an almost inconceivable event. As Noble Prize laureate and renowned psychologist Daniel Kahneman notes in his book Thinking Fast and Slow[4]: “when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.” In other words, there was no way Rodriguez could recognize from his limited experiences how devastating a massive lahar could be. In the parlance of psychology, Rodriguez had no way of updating his personal model of reality with the magnitude of destruction from lahars. I suspect he substituted what he knew – the bad political ramifications of evacuation if nothing happened – for what he did not. I was there 4 days after the event and although as a volcanologist I have seen hundreds of ancient lahar deposits, there was nothing that prepared me for what I saw at Armero – an existential experience of epic proportions.

It’s instructive to see how substitution can work. Students were asked the following questions:

How happy are you these days?

How many dates did you have last month?

There was surprisingly no correlation found among the answers suggesting that dating was not the foremost factor in the happiness of student lives. Another group of students was asked the same questions but in the reverse order:

How many dates did you have last month?

How happy are you these days?

There was a huge and significant correlation between the answers. Happiness is a difficult question to answer if even possible. But if students are primed with a question about dating and then asked their happiness status, they can equate it to their dating. It is classic substitution. Kahneman states: “the students who had just been asked about their dating did not need to think hard because they already had in their mind an answer to a related question: how happy they were with their love life. They substituted the question to which they had a readymade answer for the question they were asked.”

The heuristic is important. People often make judgments by addressing their feelings or emotions. They may ask “How do I feel about it?” rather than “What do I think about it?” substituting emotions for cognition. Combine this with the results of experiments that show we tend to “underweight” rare events that we have not experienced and disaster becomes almost inevitable. How many Wall Street advisers foresaw the financial debacle of 2008? How many FBI agents warned of an eminent attack on the World Trade Center in 2001? And even when the experts had targeted Armero as a site of destruction, it was difficult for Rodriguez to sound the alarm.

Why terrorism?

Almost the opposite happens after humans are confronted with a horrifying incident. Kahneman notes that over about a three-year period beginning in 2001 there were 236 Israeli citizens killed in suicide bombings of buses. Emphasizing that approximately 1.3 million people ride Israeli buses on any given day, the probability of dying in a bus attack is incredibly small. But that is not how Israelis saw the risk. They avoided buses and when they were forced to ride, many spent apprehensive moments surveying other riders for packages that might conceal bombs.

We know at some intellectual level that terrorists commit atrocities like bus bombings to sew fear into the fabric of a nation. They win if they disrupt a nation’s sense of security. But that still does not prevent us from associating potential harm with buses after a spate of bus attacks even when there are much greater threats (e.g., car accidents). Kahneman’s research allows him to note: “An extremely vivid image of death and damage, constantly reinforced by media attention and frequent conversations, becomes highly accessible [in our memories], especially if it is associated with a specific situation such as the sight of a bus. The emotional arousal is associative, automatic, and uncontrolled, and it produces an impulse for protective action.”

You can see how vivid images of terror might be important for our survival in hunter-gatherer societies where genetic selection was honed. Watching a saber-toothed tiger attack and kill a fellow hunter would certainly seem to fall under the heading “life altering event”: much more so than simply being told of an attack. And perhaps the resulting trauma and anxiety predisposed the spared hunter to avoid a similar attack – potentially selecting for and passing on genetically the neural circuitry that produced the emotional response. Post-traumatic stress disorder may be an avoidance strategy – “natures” way of emphasizing the significance of a terrible event.

It is easy to understand how terrorism foments fear and a demand for action. It also presents an opportunity for various constituencies of the government to initiate actions that supposedly protect us while taking away freedoms and justify immense spending under the guise of counterterrorism. Files released by Edward Snowden in 2013 identify a so-called “black budget” of $53.6 billion that targets terrorism. As of 2013, the United States had spent more than $500 billion since 9/11 fighting terrorism[5] – that’s over $2,000 per adult US citizen. Perhaps more importantly, The Heritage Foundation has documented 60 “Islamist-inspired terrorist plots against the United States” thwarted since 9/11[6]. That may seem like a significant number but as we shall see, many of these plots were done by mentally incompetent men lured into sting operations by the FBI. And the cost turns out to be a staggering 8.3 billion taxpayer dollars per plot quashed. But since the 9/11 terrorist attack that killed almost 3,000 people, only 97 victims have been murdered by Muslim extremists. Most of the deaths occurred in four well publicized attacks: the 2009 Fort Hood shooting (13 killed), the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings and subsequent shootout (5 killed including police), 2015 San Bernardino attack (14 killed), and the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting (49 killed)[7]. Your odds of being killed by a foreign-born terrorist over your lifetime are 1 in 45,808, odds that fall between being killed by a tornado (1 in 60,000) and being killed by an animal (1 in 30,167)[8]. And shouldn’t we be asking why counterterrorism funds were marked as “black budgets” which we would never have known about if it were not through the efforts of Snowden? I suspect that the government does not want us to know the astronomical amounts of money being spent to “protect” us from a handful of terrorist attacks

I don’t wish to make light of those that have died by terrorist attacks or serious efforts by various segments of the constabulary to prevent attacks, but the number of deaths by terrorism pales in comparison to other types of violent deaths. In the United States, your chances of dying in a traffic accident are astronomically higher than death from a terrorist attack. There were more than 30,000 deaths related to traffic accidents in 2015 and more in 2016[9], but there are no government initiatives to fight traffic accidents. If logic ruled our government’s decision making, some of that “terrorist” funding would go toward highway safety. We are confusing priorities because of the “emotional arousal” terrorist attacks create – which is precisely the reason our enemies use them.

In case you think resources spent to prevent another 9/11 are protecting America from copious similar attacks, think again. Once the major “easy targets” were secured, the FBI has gone to Herculanean efforts to find and arrest terrorists that may not be who the FBI says they are. The FBI now spends more on terrorism than traditional forms of crime such as financial corruption and organized crime. As of 2015, there have been about 175 arrests made by the FBI related to terrorism through their network of more than 15,000 informants (up from 1,500 in 1975): by far and away the largest network of domestic spies in history. These informants can make as much as $250,000 for every terrorist case brought to the FBI[10]. According to investigative reporter Trevor Aaronson many of the arrests of “mentally ill or economically desperate people” involve informants that are criminals and con men themselves (Aaronson has also documented cases where the FBI has used the threat of being placed on the no fly list and other unseemly leverage, including the threat of prosecution, to “encourage” Muslims to become informants). In several cases, the FBI, through its informants, has provided weapons and cash to mentally challenged or disturbed individuals to encourage them to plot terrorist attacks – only to arrest them once they take the bait. In other cases, these so-called radicals went forward with an attempted attack because they wanted the money offered by the FBI informants, not because they were committed to jihad.[11] After the arrests, the FBI, in a fashion reminiscent of Elliot Ness, announces the thwarting of another imminent terrorist attack which helps assure further funding from Congress. Isn’t this precisely what Osama bin Laden would have hoped for — massive resources being thrown at ghost terrorists?

As Aaronson points out, directly after 9/11 the G-men expected a second wave of terrorism from so-called Muslim sleeper cells. But the intense hunt for Al Qaeda leaders and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq discombobulated any central planning within potential radical Muslim networks, and the second wave never materialized. The FBI had to adapt and focused on stopping lone-wolf attacks by Muslims within the United States radicalized by the internet – the so-called home grown radical terrorists. The FBI routinely uses their sting operations on the smorgasbord of hapless individuals (many of the cases border on entrapment) to justify large budget requests to Congress. It is a vicious cycle not to mention it dupes an uncritical public. On top of everything else, while the vast array of informants search for primarily incompetent, often-times homeless mentally challenged persons, the small number of real terrorists (those capable of generating serious attacks) are sometimes not outed and go on to strike targets such as in San Bernardino or Boston.

Aaronson’s book is filled with examples of mentally handicapped, homeless, or mentally ill Muslims that were targeted by the FBI as potential lone-wolf terrorists. The FBI gets informants to contact them, supplies them with all the necessary paraphernalia for an attack, and then arrests them once they “pull the trigger” on a planted fake bomb. The recent arrest and sentencing of John T. Booker serves as an example of the continued strategy used by the FBI.

Booker, a Topeka, Kansas native converted to Islam when he was a senior in high school. In March, 2014, when he was 20, Booker posted on Facebook that he wanted to wage jihad on the United States. Not surprising, the post caught the attention of the FBI who had their informants make contact (no public information exists as to how much the informants were paid). As is typical in lone-wolf setups, the FBI informants provided Booker with inert bomb and materials and even drove him to Fort Riley where he wished to launch his attack. Once he attempted to explode the fake bomb, the FBI arrested him[12].

Booker’s public defender stated that he thought his client was mentally ill, but eventually Booker cut a plea bargain with the FBI sparing Booker from the death penalty. He pled guilty on February 3, 2016, to counts of “attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction” and “attempted destruction of government property by explosion”. He was sentenced to 30 years.

The question constantly asked by Aaronson is “would people like Booker have actually committed a crime if they were not enabled by the FBI?” There is little doubt that a seemingly mentally ill Booker felt anger and expressed that anger. But was he capable of doing harm without enablers? We will never know, but that has not kept various agencies of the government from promoting Booker as an extreme danger to society. Prosecuting Acting Assistant Attorney General Tom Beall stated: “Violent extremism is a threat to America and all its people… Our goal is to prevent violent extremists and their supporters from inspiring, financing or carrying out acts of violence.” Violent extremism? Supporters? One thing seems certain when the FBI goes to Congress with hands out, Booker will be morphed into as ruthless and cunning an adversary as the FBI can portray him to make sure it is clear they are on the job. Not only will taxpayers be footing the bill for continued seemingly exorbitant FBI funding but they will be paying to incarcerate these lone-wolf targets whether they are truly dangerous or not.

Michael German, a 16-year veteran former FBI agent told Aaronson “If you are the terrorism agent in a benign Midwestern city, and there is no terrorism problem, you don’t get to say, ‘There’s no terrorism problem here.’ You still have to have informants and produce some evidence your doing something.” Terrorist funding requires terrorist arrests.

Lone-wolf terrorist John T. Booker.

Did bin Laden win?

I am convinced with some certainty that somewhere within the archives of Congress there is a law that demands a catchy acronym for any significant Act of Congress, thus explaining the stupefying name “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act” which we know as the USA PATRIOT act. bin Laden must have been the happiest terrorist within the caliphate when the act was rushed through Congress and signed by George W. Bush on October 26, 2001! What could delight a terrorist more than seeing a free democracy overreact to 9/11 by diminishing the republics freedoms? I am not just alluding to the inconvenience of waiting in massive lines at the airport to have your body scanned or sending shoes through x-ray machines so we can feel secure knowing there is no shoe bomber on our jets. No, we can thank the Patriot Act for enabling the National Security Agency (NSA) to establish its massive phone data collection activities (which supposedly were stopped in 2015 after the uproar caused by Snowden exposing the secret operation – now the phone companies collect the data).

In late 2013, the New York Times reported that the CIA, under the guise of the Patriot Act, is collecting data on financial transactions both into and out of the United States[13]. The Times inferred that the secret spying operation offered “evidence that the extent of government data collection programs is not fully known and that the national debate over privacy and security may be incomplete.”

You need to know that prior to 9/11, deciding to investigate anyone required credible evidence that the suspect was involved in a crime. Not so anymore. After the Patriot Act, the FBI could essentially use profiling on the basis of religious affiliation to develop persons of interest. But as I have emphasized, the targets are oftentimes petty miscreants. Aaronson states: “While the cases involve plots that sound dangerous – about bombing skyscrapers and synagogues and crowded public squares – if you dig deeper, you see that many of the government’s alleged terrorists seem hopeless; they are almost always young and down on their luck, penniless, without much promise in their lives, easily susceptible to a strong-willed informant’s influence. They’re often times blustery punks.”

It seems to me that one of the goals of America’s war on terrorism should be to protect the freedoms guaranteed by our democracy — that is, to take us back to a time prior to 9/11 when we were not saddled with such things as Patriot Acts which spy on citizens or when we did not spend massive amounts of money on secret programs. The goals definitely should not be to use terrorism as an opportunity to build up secret administrative budgets in the search for “ghost” terrorists while deemphasizing other forms of crime. Spending to protect American citizens should be commensurate with the threat – not the perceived threat as Kahneman and Aaronson have so eloquently described.

[1] Armero tragedy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armero_tragedy

[2] Voight, B., 1990, The 1985 Nevado del Ruiz volcano catastrophe: anatomy and retrospection: J. Volcanol Geotherm. Res., v. 42, p. 151-188.

[3] Op cit. Voight 1990

[4] Kahneman, D., 2013, Thinking Fast and Slow: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 499p.

[5] Gellman, B. and Miller, G., 2013, ‘Black Budget’ summary details U.S. spy network’s successes, failures and objectives: Washington Post, Aug. 29.

[6] 60-terrorist plots since 9/11: http://www.heritage.org/terrorism/report/60-terrorist-plots-911-continued-lessons-domestic-counterterrorism#_ftn1

[7] Terrorism in the United States: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terrorism_in_the_United_States#2000.E2.80.9309

[8] How likely are foreign terrorists likely to kill Americans: http://www.businessinsider.com/death-risk-statistics-terrorism-disease-accidents-2017-1

[9] https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html

[10] Trevor Aaronson TED talk, 2015, https://www.ted.com/talks/trevor_aaronson_how_this_fbi_strategy_is_actually_creating_us_based_terrorists

[11] Aaronson, T., 2015, How the FBI strategy is actively creating US-based terrorists, TED, https://www.ted.com/talks/trevor_aaronson_how_this_fbi_strategy_is_actually_creating_us_based_terrorists#t-53317

[12] The Kansas City Star, 2017, http://www.kansascity.com/news/local/crime/article163344123.html

[13] New York Times, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/15/us/cia-collecting-data-on-international-money-transfers-officials-say.html