After the Madrid terrorist bombing on March 11, 2004, a latent fingerprint was found on a bag containing detonating devices. The Spanish National Police agreed to share the print with various police agencies. The FBI subsequently turned up 20 possible matches from their database. One of the matches led them to their chief suspect, Brandon Mayfield, because of his ties with the Portland Seven (Mayfield, a lawyer, represented one of the seven American Muslims found guilty of trying to go to Afghanistan to fight with the Taliban in an unrelated child custody case) and his conversion to Islam (Mayfield was in the FBI database because of his arrest for burglary in 1984 and his military service). FBI Senior Fingerprint Examiner Terry Green considered “the [fingerprint] match to be a 100% identification”1. Supervisory Fingerprint Specialist Michael Wieners and Unit Chief, Latent Print Unit, John T. Massey with more than 30 years experience “verified” Green’s match according to the referenced court documents. Massey had been reprimanded by the FBI in 1969 and 1974 for making “false attributions” according to the Seattle Times2. Mayfield was arrested and held for more than 2 weeks as a material witness but was never charged while the FBI argued with the Spanish National Police about the veracity of their identification. Apparently the FBI ignored Mayfield’s protests that he did not have a passport and had not been out of the country in ten years. They also initiated surveillance of his family by tapping his phone, bugging his home, and breaking into his home on at least two occasions3. All legal under the relatively new Patriot Act.

Meanwhile in Spain, the Spanish National Police had done their own fingerprint analysis and eventually concluded that the print matched an Algerian living in Spain — Ouhnane Daoud. But the FBI was undeterred. The New York Times4 reported that the FBI sent fingerprint examiners to Madrid to convince the Spanish that Mayfield was their man. The FBI outright refused to examine evidence the Spanish had and according to the Times “relentlessly pressed their case anyway, explaining away stark proof of a flawed link — including what the Spanish described as tell-tale forensic signs — and seemingly refusing to accept the notion that they were mistaken.”

The FBI finally released Mayfield and followed with a rare apology for the mistaken arrest. Mayfield subsequently sued, and American taxpayers shelled out $2 million when the FBI settled the case. More importantly, the FBI debacle occurred during a debate among academics, government agencies, and within the courts about the “error rate” associated with fingerprint analyses5. But before I address the specific problems with fingerprint identification let’s talk about the Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals (1993) court case. The details are fairly banal and would have been meaningless to this essay except for the fact that it reached the Supreme Court and established what is now referred to as the Daubert standard for admitting expert witness testimony into the federal courts6. In summay, the judge is responsible (a gatekeeper in Daubert parlance) for making sure that expert witness testimony is based on scientific knowledge7 Furthermore, the judge must make sure the information from the witness is scientifically reliable. That is, the scientific knowledge must be shown to be the product of a sound scientific method. Finally the judge must ensure that the testimony is relevant to the proceedings which loosely translated means the testimony should be the product of what scientists do – form hypotheses, test hypotheses empirically, publish results in peer-reviewed journals, and determine the error in the method involved when possible. Finally the judge should make a determination of the degree the research is accepted by the scientific community8.

“No fingerprint is identical” – it has become almost a law of nature within forensic fingerprint laboratories. But no one knows whether it is true or not. That has not stopped the FBI from maintaining the facade. In a handbook published by the FBI in 19859 they state: “Of all the methods of identification, fingerprinting alone has proved to be both infallible and feasible”. I think that fingerprints are an exceptionally good tool in the arsenal of weapons against crime, but it is essentially unscientific to perpetuate infallibility. The fact is that the statement “all fingerprints are not identical” is logically unfalsifiable10. And the more scientists argued against the infallibility of fingerprinting the more the FBI became entrenched in their position after the Mayfield mistake11. Take, for example, what Massey said shortly after the Mayfield case: “I’ll preach fingerprints till I die. They’re infallible12.” It may be true that no fingerprints are perfectly alike (I suspect it is true) but it is also true that no fingerprint of the same finger is alike. The National Academy of Sciences asserted that “The impression left by a given finger will differ every time, because of inevitable variations in pressure, which change the degree of contact between each part of the ridge structure and the impressions medium13.” The point therefore becomes not if all fingerprints are unique but whether laboratories have the abilities to distinguish between similar prints, and if they do, what is the error in making that determination.

U.S. District Judge Louis H. Pollak ruled in a January, 2002, murder case that fingerprint analyses did not meet the Daubert standards. He reversed his decision after a three-day hearing. Donald Kennedy, Editor-in-Chief of Science opined “It’s not that fingerprint analysis is unreliable. The problem rather, is that its reliability is unverified either by statistical models of fingerprint variation or by consistent data on error rates14 15.” As one might expect, the response by the FBI and federal prosecutors to Pollak’s original ruling and subsequent criticism was a united frontal attack not based on statistical analyses verifying the reliability of fingerprint identification but the infallibility of the process based on more than 100 years of fingerprint identification conducted by the FBI and other agencies around the world. The FBI actually argued that the error rate was zero. FBI agent Stephen Meagher stated during the Daubert hearing16, to Lesley Stahl during an interview on 60 Minutes17, and to Steve Berry of the Los Angeles Times during an interview18 that the latent print identification “error rate is zero”. How can the error rate be zero when documented cases of error like Mayfield exist? Even condom companies give the chance of pregnancy when using their product.

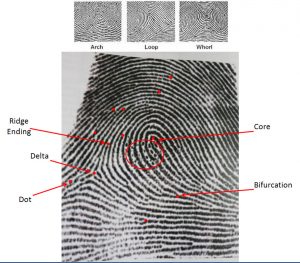

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences through their committee The National Research Council produced a report on how forensic science (including fingerprinting) could be strengthened19. Perhaps the most eye-opening conclusion of the report is that analyzing fingerprints is subjective. It is worth quoting their entire statement: “thresholds based on counting the number of features [see diagram below] that correspond, lauded by some as being more “objective,” are still based on primarily subjective criteria — an examiner must have the visual expertise to discern the features (most important in low-clarity prints) and must determine that they are indeed in agreement. A simple point count is insufficient for characterizing the detail present in a latent print; more nuanced criteria are needed, and, in fact, likely can be determined… the friction ridge community actively discourages its members from testifying in terms of probability of a match; when a latent print examiner testifies that two impressions “match,” they [sic] are communicating the notion that the prints could not possibly have come from two different individuals.” The Research Council was particularly harsh on the ACE-V method (see the diagram below) used to identify fingerprint matches: “The method, and the performance of those who use it, are inextricably linked,and both involve multiple sources of error (e.g., errors in executing the process steps, as well as errors in human judgment).” The statement is particularly disconcerting because, as the Research Council notes, the analyses are typically performed by both accredited and unaccredited crime laboratories or even “private practice consultants.”

The fingerprint community in the United States uses a technique known via an acronym ACE-V – analyses, comparison, evaluation, and verification. I give an example here to emphasize the basic cornerstone of the process which involves comparison of friction-ridge patterns on a latent fingerprint to known fingerprints (called exemplar prints). Fingerprints come in three basic patterns: arches, loops, and whorls as shown at the top of the diagram. The objective in the analysis is to find points (also called minutiae) defined by various patterns formed by the ridges. The important varieties are shown above. For example, a bifurcation point is defined by the split of a single ridge into two ridges. I have shown various points on the example fingerprint. Once these points are ascertained by the examiner, the points are used to match to similar points in the exemplars in their relative spatial locations. It should be obvious that the interpretation of points can be problematic and is subjective. For example, note the region circled where there are many “dots” which may be related to ridges or may be due to contaminants. There is still no standard used in the United States for the number of matching points required to obtain a “match” (although individual laboratories do set standards). Computer algorithms, if used, provide a number of potential matches and examiners determine which of the potential matches, if any, is correct. The method appears straight forward but in practice examiners have trouble agreeing even on the number of points due to the size of the latent print (on average latent prints are typically one fifth of the surface of an exemplar print), smudges and smearing, the quality of the surface, the pressure of the finger on the surface, etc.20 There is another technique developed in 2005 called Ridges-in-Sequence system (RIS)21. For a more detailed description of latent fingerprint matching see Challenges to Fingerprints by Lyn and Ralph Norman Haber 22

The fingerprint community in the United States uses a technique known via an acronym ACE-V – analyses, comparison, evaluation, and verification. I give an example here to emphasize the basic cornerstone of the process which involves comparison of friction-ridge patterns on a latent fingerprint to known fingerprints (called exemplar prints). Fingerprints come in three basic patterns: arches, loops, and whorls as shown at the top of the diagram. The objective in the analysis is to find points (also called minutiae) defined by various patterns formed by the ridges. The important varieties are shown above. For example, a bifurcation point is defined by the split of a single ridge into two ridges. I have shown various points on the example fingerprint. Once these points are ascertained by the examiner, the points are used to match to similar points in the exemplars in their relative spatial locations. It should be obvious that the interpretation of points can be problematic and is subjective. For example, note the region circled where there are many “dots” which may be related to ridges or may be due to contaminants. There is still no standard used in the United States for the number of matching points required to obtain a “match” (although individual laboratories do set standards). Computer algorithms, if used, provide a number of potential matches and examiners determine which of the potential matches, if any, is correct. The method appears straight forward but in practice examiners have trouble agreeing even on the number of points due to the size of the latent print (on average latent prints are typically one fifth of the surface of an exemplar print), smudges and smearing, the quality of the surface, the pressure of the finger on the surface, etc.20 There is another technique developed in 2005 called Ridges-in-Sequence system (RIS)21. For a more detailed description of latent fingerprint matching see Challenges to Fingerprints by Lyn and Ralph Norman Haber 22

Now you might be thinking that the Mayfield case was unusual given the FBI and other agencies promote infallibility, but Mayfield seems to be the tip of the iceberg! Simon Cole of the University of California, Irvine23 has documented 27 cases of misidentification (Cole excluded cases of matches related to outright fraud) up through 2004 and underscores the high probability of many more incorrect undetected cases because of the relatively large number of documented mistakes that have slipped through the cracks (Cole uses the term “fortuity” of the discoveries of misidentification) — particularly when the FBI and other agencies are very tight lipped about detailing how they arrive at their conclusions when there is a match. These are quite serious cases involving people that spent time in prison for wrongful charges related to homicides, rape, terrorist attacks, and a host of other crimes.

It is worth looking at the Commonwealth v. Cowans case because it represents the first fingerprint-related case overturned on DNA evidence via the Innocence Project. On May 30, 1997, a police officer in Boston was shot twice by an assailant using the officers own revolver. The surviving officer eventually identified Stephen Cowans from a group of eight photographs and then from a lineup. An eye-witness that observed the shooting from a second story window also fingered Cowans in a lineup. The assailant, after leaving the scene of the crime, forcibly entered a home where he got a glass of water from a mug. The family present in the home spent the most time with the assailant and, revealingly, did not identify him in a lineup. The police obtained a latent print from the mug and fingerprint analyzers matched it to Cowans24. The conflict between eyewitness’ testimonies made the fingerprint match pivotal and led to a guilty verdict. After five years in prison, Cowans was exonerated on DNA evidence from the mug that showed he could not have committed the crime.

What do we know about the error (or error rate) in fingerprint analyses? Recently, Ralph and Lyn Haber of Human Factors Consultants have compiled a list of 13 studies (that meet their criteria through mid-2013) that review attempts to ascertain the error rate in fingerprint identification25. In the ACE-V method (see diagram above) the examiner decides whether a latent print is of high enough quality to use for comparison (I emphasize the subjectivity of the examination – there are no rules for documentation). The examiner can conclude that the latent print matches an exemplar, making an individualization (identification), she can exclude the exemplar print (exclusion – the latent does not match), or she can decide that there is not enough detail to warrant a conclusion26. The first thing to point out is that no study has been done where the examiners did not know they were being tested. This poses a huge problem because examiners tend to determine more prints inconclusive when being examined27. Keeping the bias in mind, let’s look in detail at the results of one of the larger studies reviewed by the Habers.

The most pertinent extensive study was done by Ulery et al.28. They tested 169 “highly trained” examiners with 100 latent and exemplar prints (randomly mixed for each examiner with latent-exemplar pairs that did not match and those that did match). Astoundingly, for pairs of latents that matched exemplars, only 45% were correctly identified. The rest were either misidentified (13% were excluded that should have been matched and a whopping 42% found to be inconclusive that should have been matched). I recognize that when examiners are being tested they have a tendency to exclude prints that they might otherwise attempt to identify, but even with this in mind, the rate is staggering. How many prints that should be matched are going unmatched in the plethora of fingerprint laboratories around the country? Put in another way, how many guilty perpetrators are set free on the basis of the inability of examiners to match prints? Regarding the pairs of latent and exemplar prints that did not match, there were six individualized (matched) that should not have been — a 0.1% error. Even if the error is representative of examiners in general (and there is plenty of reason to believe the error rate is higher according to the Habers), it is too high. Put another way, if 100,000 prints are matched with a 0.1 percent error rate, 100 individuals are going to be wrongly “fingered” as a perpetrator. And the way juries ascribe infallibility to fingerprint matches, 100 innocent people are going to jail.

There are a host of problems with the Ulery study including many design flaws. For one thing, the only way to properly ascertain error is through submitting “standards” as blinds within the normal process of fingerprint identification (making sure the examiners do not know they are attempting to match known latent prints). But there are many complications involved in the procedure that begins with not having any agreed upon standards or even rules to establish what a standard is29. I have had some significant and prescient discussions with Lyn Haber on the issues. Haber zeroed in on the problems at the elementary level: “At present, there is no single system for describing the characteristics of a latent. Research data shows [sic] that examiners disagree about which characteristics are present in a print.” In other words, there is no cutoff “value” that determines when a latent print is “of such poor quality that it shouldn’t be used”. Haber also notes that “specific variables that cause each impression of a finger to differ have not been studied”.

The obvious next step would be to have a “come to Jesus” meeting of the top professionals in the field along with scientists like the Habers to standardize the process. That’s a great idea, but none of the laboratory “players” are interested in cooperating — they are intransigent. The most salient point Haber makes in my opinion is the desire by various agencies to actively keep the error unknowable. She states that “The FBI and other fingerprint examiners do not wish error rates to be discovered or discoverable. Examiners genuinely believe their word is the “gold standard” of accuracy [but we most assuredly know they make mistakes] . Nearly all research is carried out by examiners, designed by them, the purpose being to show that they are accurate. There is no research culture among forensic examiners. Very very few have any scientific training. Getting the players to agree to the tests is a major challenge in forensic disciplines.” I must conclude that the only way the problem will be solved is for Congress to step in and demand that the FBI admit they can make mistakes, work with scientists to establish standards, and adequately and continuously test laboratories (including their own) throughout the country. While we wait, the innocent are most likely being sent to jail and many guilty go free.

A former FBI agent still working as a consultant (he preferred to remain anonymous) candidly told me that the FBI knows the accuracy of various computer algorithms that match latents to exemplars. He stated “When the trade studies were being run to determine the best algorithm to use for both normal fingerprint auto identification and latent identification (two separate studies) there were known sample sets against which all algorithms were run and then after the tests the statistical conclusions were analyzed and recommendations made as to which algorithm(s) should be used in the FBI’s new Next Generation Identification (NGI) capability.” But when I asked him if the data were available he said absolutely not “because the information is proprietary” (the NGI is the first stage in the FBIs fingerprint identification process – they match with the computer and send the latent with closest matches to the analyzers). Asking for the computer error rate should not be proprietary – the public does not have to know the algorithm to understand the error on the algorithm.

Of course, computer analyses bring an additional wrinkle to the already complex determination of error. Haber states “Current estimates are such that automated search systems are used in about 50% of fingerprint cases. Almost nothing is known about their impact on accuracy/error rates. Different systems use different, proprietary algorithms, so if you submit the same latent to different systems (knowing the true exemplar is in the data base), systems will or will not produce the correct target, and will rank it differently… I am intrigued by the problem that as databases increase in size, the probability of a similar but incorrect exemplar increases. That is, in addition to latents being confusable, exemplars are.” I would only emphasize that the FBI seems to know error rates on the algorithms but has not, as far as I know, released that data.

To be fair, I would like to give the reader a view from the FBI perspective. Here is what the former FBI agent had to say when I showed him comments made by various researchers: “When a latent is run the system generally produces 20 potential candidates based on computer comparison of the latent to a known print from an arrest, civil permit application where retention of prints is permissible under the law etc. It is then the responsibility of the examiner from the entity that submitted the latent to review the potential candidates to look for a match. Even with the examiner making such a ‘match’ the normal procedure is to follow up with investigation to corroborate other evidence to support/confirm the ‘match’. I think only a foolish prosecutor would go to court based solely on a latent ‘match’… it would not be good form to be in court based on a latent ‘match’ only to find out the person to whom the ‘match’ was attached was in prison during the time of the crime in question and thus could not have been the perpetrator.” Mind you, he is a personal friend whom I respect so I don’t criticize him lightly, but he is touting the standard line. Haber notes that in the majority of cases she deals with as a consultant “the only evidence is a latent”.

I suspect that the FBI along with lesser facilities does not want anyone addressing error because the courts may not view fingerprints as reliable, no, infallible, as they currently do, and the FBI might have to go back and review cases where mistaken matches are evident. As a research geochemist I have always attempted to carefully determine the error involved in my rock analyses so that my research would be respected, reliable, and a hypothesis drawn from the research would be based on reality. We are talking about extraordinary procedures to determine error on rock analyses. No one is going to jail if I am wrong. I will leave you with Lyn Haber’s words of frustration: “No lab wants to expose that its examiners make mistakes. The labs HAVE data: when verifiers disagree with a first examiner’s conclusion, one of them is wrong. These data are totally inaccessible… I think that highly skilled, careful examiners rarely make mistakes. Unfortunately, those are the outliers. I expect erroneous identifications attested to in court run between 10 and 15%. That is a wild guess, based on nothing but intuition! As Ralph [Haber] points out, 95% of cases do not go to court. The defendant pleads. So the vast majority of fingerprint cases go unchallenged and untested. Who knows what the error rate is?… Law enforcement wants to solve crimes. Recidivism has such a high percent, that the police attitude is, If [sic] the guy didn’t commit this crime, he committed some other one. Also, in many states, fingerprint labs get a bonus for every case they solve above a quota… The research data so far consistently show that false negatives occur far more frequently than false positives, that is, a guilty person goes free to commit another crime. The research data also show — and this is probably an artifact — that more than half of identifications are missed, the examiner says Inconclusive. If you step back and ask, Are fingerprints a useful technique for catching criminals, [sic] I think not! (These comments do not apply to ten-print to ten-print matching.)”

- The quote is from a government affidavit – Application for Material Witness Order and Warrant Regarding Witness: Brandon Bieri Mayfield, In re Federal Grand Jury Proceedings 03-01, 337 F. Supp. 2d 1218 (D. Or. 2004) (No. 04-MC-9071)

- Heath, David (2004) FBI’s Handling of Fingerprint Case Criticized, Seattle Times, June 1

- Wikipedia

- Kershaw, Sarah (2004) Spain and U.S. at Odds on Mistaken Terror Arrest, NY Times, June 5

- see the following for more details: Cole, Simon (2005) More than zero: Accounting for error in latent fingerprint identification: The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 95, 985

- Actually the Daubert standard comes not only from Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals but also General Electric Co. v. Joiner and Kumho Tire Co. v. Carmichael

- I can’t help but wonder what it was based on prior to Daubert.

- It remains a mystery to me as to how a judge would have the training and background to ascertain if an expert witness meets the Daubert standard, but perhaps that is best left for another essay

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (1985) The Science of Fingerprints: Classification and Uses

- What I mean by unfalsifiable is that even if we could analyze all the fingerprints of all living and dead people and found no match, we still could not be absolutely certain that someone might be born someday with a fingerprint that would match someone else. Some might think that this is technical science speak but in order to qualify as science the rules of logic must be rigorously applied.

- Cole, Simon (2007) The fingerprint controversy: Skeptical Inquirer, July/August, 41

- Scarborough, Steve (2004) They Keep Putting Fingerprints in Print, Weekly Detail, Dec. 13

- National Research Council of the National Academies (2009) Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward: The National Academy of Science Press

- Error rate as used in the Daubert standard is somewhat confusing in scientific terms. Scientist usually determine the error in their analyses by comparing a true value to the measured value, inserting blanks that measure contamination, and usually doing up to three analyses of the same sample to provide a standard deviation about the mean of potential error for the other samples analyzed. For example, when measuring the chemistry of rocks collected in the field, my students and I have used three controls on analyses: 1) Standards which are rock samples with known concentrations determined from many analyses in different laboratories by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2) what are commonly referred to as “blanks” (the geochemist does all the chemical procedures she would do without adding a rock sample in an attempt to measure contamination), and three analyzing a few samples up to three times to determine variations. All samples are “blind” – unknown to the analyzers. The ultimate goal is to get a handle on the accuracy and precision of the analyses. These are tried and true methods and as I argue in this essay, a similar approach should be taken for fingerprint analyses.

- Kennedy, Donald (2003) Forensic science: Oxymoron?, Science, 302, 1625.

- Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993) 509 US 579, 589

- Stahl, Lesley (2003) Fingerprints 60 Minutes, Jan. 5.

- Berry, Steve (2002) Pointing a Finger: Los Angeles Time, Feb. 26.

- see ref. 13

- Haber, L. and Haber, R. N. (2004) Error rates for human latent fingerprint examiners: In Ratha, N. and Bolle, R., Automatic Fingerprint Recognition Systems, Springer

- Ashbaugh, D. R. 2005 Proposal for ridge-in-sequence: http://onin.com/fp/ridgeology.pdf

- Haber, L. and Haber, R. N. (2009) Challenges to Fingerprints: Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company

- see ref. 5

- One of the biggest criticism of the fingerprint community comes from the lack of blind tests — fingerprint analyzers often know the details of the case. Study after study has shown that positive results are obtained more frequently if a perpetrator is known to the forensic analyzers – called expectation bias: see, for example, Risinger, M. D. et al. (2002) The Daubert/Kumbo Implications of observer effects in forensic science: Hidden Problems of Expectation and Suggestions, 90 California Law Review

- Haber, R. N. and Haber, N. (2014) Experimental results of fingerprint comparison validity and reliability: A review and critical analysis: Science and Justice, 54, 375

- see The Report of the Expert Working Group on Human Factors in Latent Print Analysis (2012) Latent Print Examination and Human Factors: Improving the Practice through a Systems Approach: National Institute of Technology

- see ref. 24

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Buscaglia, J., and Roberts, M. A. (2011) Accuracy and reliability of forensic latent fingerprint decisions: Proc. National Academy of Science of the U.S.

- see ref. 14